Rock Island, IL –-(Ammoland.com)- In the Rock Island Auction Company Preview Hall preparations are already being made for our September 2013 Premiere Auction.

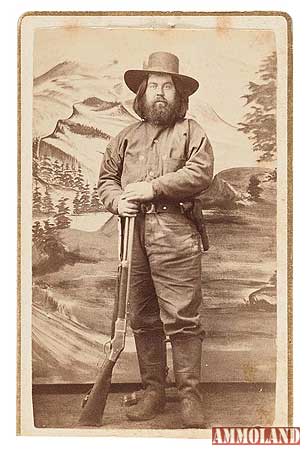

Displays are arranged, guns are placed, cases are filled, and items glint under fluorescent lights. Among all the revolvers, war trophies, lever actions, and antiques is a curious, small photo.

It is of a sturdy man posing in a portrait studio with rifle present and revolver on his hip. It seems a rather simple item, but the story behind the man in the photo is anything but simple, thanks to a rather adventurous life.

The story of Robert Pilson is an interesting one that we may never know in its entirety. We are told that he lived a life of “many deeds of daring in his younger days,” and “his many eccentricities during the closing years of his life,” but very little more. However, even if we know little of Pilson individually, we may make certain assumptions of his life courtesy of his occupation. He was a scout for the U.S. government and during his era that line of work would have some serious adventure to it.

What we do know of Pilson is so compelling, one can scarcely imagine what the rest of his life was like if it was as full of daring as our source implies.

Robert Pilson was born in 1840 in Woolwich, England and came to the United States at age 4, but an obituary from the Chicago Tribune states that he was born in La Salle, IL, however the rumor of his American birth is disproved by later census documents. We are told he received his education in La Salle before moving to Moberly, Missouri “where he attained the age of manhood.” Reminiscent of the tales of young Abraham Lincoln, Pilson could wrestle and defeat any man for miles in any direction. He was “a giant in size and in strength,” often performing feats of strength for the delight of onlookers. This resulted in him receiving several offers “to travel on a big salary,” but he refused every last one of them.

Early in the 1860’s he arrived in western Nebraska, but would later end up in Fort Laramie, Wyoming where he would take up employment as a scout for the U.S. government. While that last sentence takes us right up to what we know about Pilson, it leaves out a terrible amount of detail. Why did he move to Nebraska? What pushed him even further west in Wyoming? Why take work as a scout? Like many men of his time was there an even more lucrative profession that awaited him out west? We may not know what spurred his move west, but it would be safe to say that prior to his work at Ft. Laramie, that Pilson was a trapper. Many scouts were former trappers or hunters. However, this work would have been in addition to his work as a farmer, which is documented in an 1870 census of LaSalle County, Illinois.

Trappers knew how to survive on the land, what to eat, what not to eat, how to find water, how to track or “read sign,” how to hunt, how to find paths, and they knew the country. This knowledge would not only be immensely valuable to themselves, but also to their later employers who would depend on them as scouts not only for proper navigation, but also for sustenance and avoiding American Indians. It would also be of value to parties interested in taming the West. Scouts would be needed by settlers, soldiers, cartographers, railroad companies, and scientists all of whom had an interest in exploring, documenting, and blazing the trails in the new frontier. However, the profession was not without its hazards, on the contrary, scouts would face death or survival situations almost daily. Scouting was what George A. Custer once described as “congenial employment, most often leading to a terrible death.”

On the assumption of his former occupation as a trapper, we can also safely say that Pilson was likely engaged in selling pelts. He would have entered the profession too late to capitalize on the beaver trade, a boom thanks to a European men’s hat trend, which faded in the 1840s, but could still have made an excellent living for himself. Working for a fur company, one could receive a guaranteed salary of $200 per year, but in a good season a trapper could make ten times that sum. To put that in perspective, an East Coast carpenter would expect to earn not a penny over $550. Given these figures, it would be hard to imagine him earning more money working for the government in a fort, but as a scout he could earn much more. A trip from Laramie to Fort Hall, ID, a trip over 500 miles, could be contracted out for around $250 in 1842 and well known tracker William Comstock was paid nearly $125 each month for his services as a scout in 1868, almost 10 times the rate of a private soldier.

In this trapper’s life, Pilson might have had his first experience with American Indians. There are many documented instances of trappers getting into scrapes with the locals. Indians would take the trapped animals, steal pelts, and even kill trappers. These accounts are largely accountable thanks to their sheer numbers and consistency. However, trappers are also well-known, by their own volition, of being hostile to the Indians in order to show they were not to be pushed around. These first occupations of Pilson’s tell us that he had excellent survival skills, was a strong, robust man, and may have developed a distaste for American Indians early in his adult life.

Our next documented event of Pilson says that while working at Ft. Laramie, “up to this time he had not weighed over 200 pounds, but he now commenced to take on flesh so rapidly that it soon became a difficult problem to find horses of sufficient strength and endurance to carry the heavy-weight scout.” It appears that life inside the fort walls had made Robert soft, though “soft” living at that time would still be considered borderline brutal by today’s standards. However, it appears this gluttony did not hasten him in his duties as it is noted that, “Pilson was valuable to the commandant of the post, for his great courage and natural liking for dangerous and difficult undertakings placed him in constant demand.” One day, in the course of his routine scouting expeditions of enemy (Sioux) territory, Pilson was in the midst of a two day trek among the camps of the Sioux. It being a lovely September afternoon, he decided to lay down for a much-needed rest within a group of rocks near what is now the town of Casper, Wyoming. He was awoken violently as a group of nine Sioux warriors set upon him and tied him up before he had the chance to resist. The imposing figure was then lashed to a horse and lead away from the white man’s world to the head camp of the Sioux tribe, “situated in the Bad Lands, near Pine Ridge, Nebraska.”

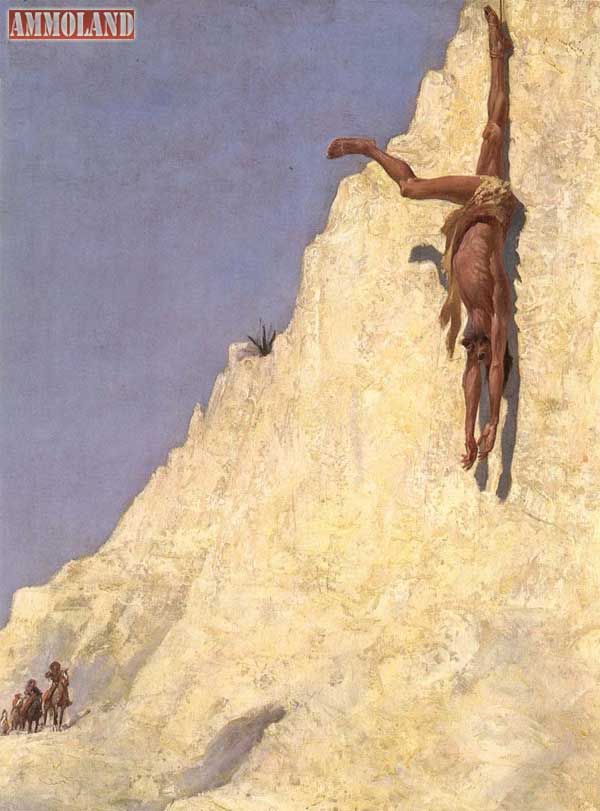

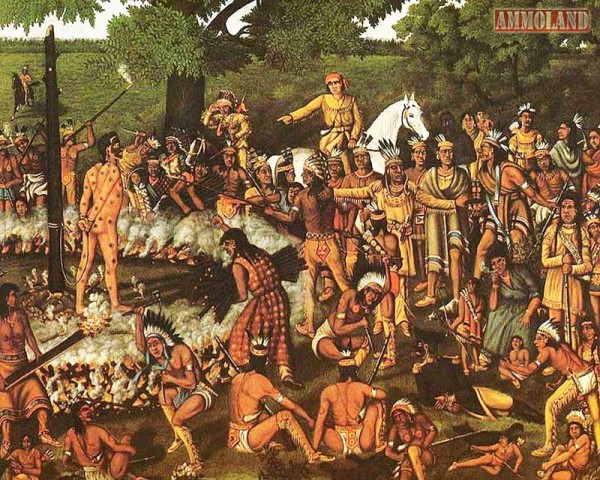

One can only imagine the thoughts and fear racing through Robert’s head. His trapping days had undoubtedly regaled him with tales of what American Indians would do to prisoners. Stories abounded of prisoners being scalped, burned with charred woods, heated stone tools, or white-hot metals, dismembered, disemboweled, blinded, burned in various ways, flayed alive, mutilated, cannibalized, bound with wet rawhide (which would tightened as it dried), and countless other fates. Torture sessions were not short exercises and could last days. The American Indians could be creative captors and Robert had likely heard the worst. All these things were certainly flashing before his eyes as he was helplessly lead to the what would likely be the last place he would see alive.

similar ones no doubt filled the young scout’s mind.

When the band arrived back at their village they discovered that the chief was away. In his absence the Indians tied Pilson to a stake and began a three day marathon of torture and pain on the scout. Tomahawks and knives were thrown at his head and body, but Pilson bore his torture with resolute courage and a fortified constitution. He was hit directly on several occasions with the deadly instruments, but never uttered a word, instead choosing to smile at his captors. Other tribe members came round and would amuse themselves by marring Pilson’s lumpy anatomy with burning sticks and small torches. At the end of three days, the Indians became frightened of their mysterious prisoner. They could not understand how he did not show the signs of the torture inflicted upon him. A council was called, presided over by the medicine man in lieu of the chief. The medicine man determined that the white man was no ordinary white man, but an evil spirit who would certainly destroy them all if they continued their slow execution. Immediately, our scout was untied, his wounds dressed, and he was allowed to heal.

While Pilson was on the mend, the chief returned to the village and was apprised of what had transpired in his absence. Whether from fear or genuine admiration, the chief treated Pilson with nothing but the utmost kindness until he left; nothing would be too good for their guest. Once finally recovered, Pilson was given freedom within the camp, and when he finally decided to depart the scout was implored in earnest to return again soon to pay the village another visit.

“After these experiences Pilson was in several Indian wars, the last being in ’78, when the Utes raided the Lower Platte valley.” That is the next line in the story from the original source and it gives the impression that ol’ Robbie was after a little bit of vengeance on those that had made him suffer. This is a comical twist considering that earlier in the source material it is claimed that the events of his capture and torture, “tested his nerve and at the same time placed him upon friendly terms with the Indians,” and implies that they parted ways like old friends. Generally, one does not go to war against people they are on “friendly terms” with. However, it is noted that Pilson “learned several Indian languages and served the government as an interpreter several times when Uncle Sam was negotiating with the redmen.”

Perhaps he figured the best way to get back at the American Indians was to help the U.S. drive them off their lands and into reservations.

The last ten years of his life, Pilson was a cattleman and was known to do business with Lord Ralli, a wealthy Englishman. The only other text that I could find that specifically documents Pilson states that “Bob Pilson, (a) jovial 350-pound cattleman,” bought the Cow Creek ranch in 1888 from one William F. Swan. The role of a cattleman seems an odd twist in the life of Pilson. Having once been a scout paid to help the homesteaders, his job in livestock almost certainly made him an enemy of many homesteaders as tensions between the two groups mounted in the late 19th century. Was this just another example of money motivating the man?

At the end of his life at 1:42 p.m. on March 23, 1899, Robert “Bob” Pilson was 59 years of age and weighed a Toledo-tipping 529 pounds. Thankfully, nine years before his death he had a special coffin built for himself with his own specifications in mind. Again, sources differ on the particulars, but it was an extra-large coffin, adorned with oak and silk, and reinforced in several ways to ensure it could properly carry its solitary passenger. The aforementioned “jovial” nature must have followed Bob the rest of his days. An obituary from the Saratoga Sun states,

“An hour before the appointed time for the funeral, people began to assemble at the church. Every seat was filled and at the last, there was not even standing room. There were neither kith nor kin present to act in the capacity of mourners – not a soul to drop a tear. Yet the occasion was one of the most solemn that has ever been held in any church. It was such an out pouring of people and such a manifestation of silent sympathy that would have astonished the deceased could he have seen it, for he did not regard himself as having many friends… He was very eccentric, scrupulously honest, very kind-hearted and sympathetic. He has been a familiar figure on our streets for many years and his presence will be missed and regretted by all who knew him…He was one of the best known characters in the state, and his death removes from our midst one of the landmarks of the valley. Not a man who ever knew him but will express regret when he hears of his death, and pay that silent tribute which we all pay to the dead.”

Robert Pilson is a fascinating character despite that we know so little about him! He had a love for adventure, examples of bravery and courage, a mysterious transition into life after the Old West, a love of food and laughter, a keen business sense, and a large waistline. One can only imagine the other tales of daring-do associated with his scouting days and the Indian wars. He is yet another historical figure that Rock Island Auction Company is honored to have in this auction.

- https://archive.org/stream/annalsofwyom15141943wyom/annalsofwyom15141943wyom_djvu.txt

- https://www.findagrave.com/cgi-bin/fg.cgi?page=gr&GRid=45739022

- https://www.rootsweb.ancestry.com/~illasall/1870census/dimmick.htm

- Wheeler, Keith. The Old West: The Scouts. Alexandria, VA: Time-Life, 1978. Print.

About:

Rock Island Auction Company has been solely owned and operated by Patrick Hogan. This company was conceived on the idea that both the sellers and buyers should be completely informed and provided a professional venue for a true auction. After working with two other auction companies, Mr. Hogan began Rock Island Auction in 1993. Rock Island Auction Company has grown to be one of the top firearms auction houses in the nation. Under Mr. Hogan’s guidance the company has experienced growth each and every year; and he is the first to say it is his staff’s hard work and determination that have yielded such results. Visit: www.rockislandauction.com

Great, I love reading stories like this.

I was born in 1940. I have always said I was born 100 years to late. This story explains why. I hate what this country has become.