Reverend Alexander John Forsyth made a significant change in the world of firearms ignition systems. Born in 1768 to a minister in Scotland, he was educated at King’s College and followed in his father’s footsteps as a man of the cloth. A deep thinker, he often walked along the water as a calming way to collect his thoughts, sometimes thinking about his sermons; other times, thinking about firearms.

As an avid duck hunter, Forsyth lamented the inefficiency of the flintlock’s design as a hunting piece. The delay between the trigger pull, ignition of the flash pan, ignition of the main powder charge, and the actual firing of the weapon was advantageous to the ducks and not the hunter. First, the noise of the mechanism alerted the birds of something in the area; then, the resulting delay provided enough time for the birds to make an evasive maneuver and avoid being shot.

In 1805, at the age of 37, Forsyth had developed his first percussion-style lock. He went to London and showed his design to Master-General of Ordnance, Lord Moira. Impressed by the design, Moira arranged for Forsyth to take a leave of absence from his parish and was given quarters in the workshops of the Tower of London. By 1806, however, Lord Moira had been replaced by the Earl of Chatham, who did not share Lord Moira’s enthusiasm for the new design. He ordered Forsyth to remove his “rubbish” from the Tower. After leaving the Tower of London, Napoleon Bonaparte supposedly offered Forsyth £20,000 if he would bring his invention to France, but Forsyth declined.

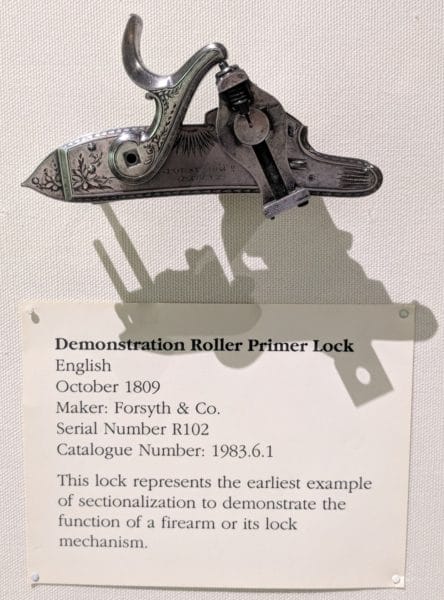

In 1807, Forsyth received a patent on his design. By 1808, with enough financial support and expert manpower from renowned gunmaker James Purdey, he opened his own firearms manufacturing firm. The company produced a number of guns using his new percussion system that utilized mercury fulminate to ignite the gunpowder.

In December 1808, he took out an ad in London’s “Morning Post” about his new business. The ad read in part:

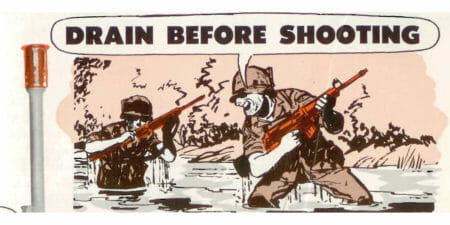

“To Sportsmen, the Patent Gun-lock invented by Mr. Forsythe [sic] is to be had at No. 10 Piccadilly, near Haymarket. Those … unacquainted with … this invention are informed that the inflammation is produced without … flint, and is much more rapid. … The lock is … completely impervious to water, or damp of any kind, and may in fact be fired under water.”

Soon, Forsyth found himself having to defend his patent against a variety of other gunmakers, most notably being renowned maker Joseph Manton. Legal battles around the percussion ignition system would lead to Forsyth’s downfall. Defending his patent in court was a costly venture; after only a handful of years in business, he returned to his parish and reclaimed his place in the pulpit.

Forsyth’s invention did not utilize the percussion cap. Instead, his sliding magazine locks operate by having the priming magazines linked to the hammer of the firearm. When the hammer is cocked, the magazine moves back over the flash pan. When in that position, a small priming charge is dispensed from the magazine into the pan. When the trigger is pulled, the magazine moves forward out of the way and the charge is detonated by a firing pin on the hammer that fits into the pan.

The most important advance to the percussion system was the creation of the copper percussion cap, which was patented in the United States in 1822 to avoid legal action by Forsyth. It wouldn’t be long before the percussion ignition system would come to dominate firearms worldwide. With a heyday much shorter than that of the flintlock, it saw considerable use until the advent of self-contained metallic cartridges in the mid- and late-19th century. Even after metallic cartridges were widely available, many still continued to carry and use their percussion firearms.

Every gun holstered in the Old West can trace its existence back to Reverend Forsyth. Without his percussion system, Shaw would not have created the percussion cap. Without the percussion cap, Samuel Colt would not have been able to create his iconic cap-and-ball revolvers. From the heavy-hitting Walker in 1847 to the Model 1851, Colt has Forsyth to thank for helping jump-start his empire and propel his name into history.

One might not expect a frustrated duck hunter and man of the cloth to be the chosen individual to usher in a new age of firearms technology. However, Reverend Alexander John Forsyth did just that. More than 100 years after his invention was created, Forsyth was still being officially honored for his contributions. In 1929, a memorial for him was placed at the Tower of London – the first time ever that a memorial to a private individual had been erected on the property. Two years later in 1931, another was placed on the Cromwell Tower at his alma mater, King’s College in Aberdeen.

In 1930, the President of the National Rifle Association of Great Britain eulogized Forsyth by saying he was “[t]he only man in the world in whose honor a salute was fired every day in the year.”

In 1806 the price of gold was, I believe, 4 or 5 British pounds. If Forsyth had sold out to Napoleon for 4 or 5 thousand ounces of gold, not only would he have been a wealthy man but we might all be speaking French today. I’m even more impressed by the concept of a “priming magazine linked to the hammer”. An important step since until then I think all repeaters were some form of lever action.

I haven’t hunted birds in over fifty years, but I appreciate Rev Forsythe’s contribution which allowed for development of modern metallic cartridges as we now know them to be.

Thank You, Sir!

Good history lesson. So jolly ole England was the forefront of today’s modern bullet design and then they turned against all guns. Strange country.

This was a good read and informative article.

From one old duck hunter to another.

Thank you for a Very interesting history lesson.