Editors Note: You can catch part 2 tomorrow, so check back same time tomorrow.

Long range shooting is kind of like throwing a baseball from right field to home plate. When you boil down all the complexity, you really only have to worry about two things: how far the bullet falls before it hits the target and how far the wind blows it sideways.

If you want to make your head hurt, you can add in more variables like moving targets, rotation of the earth, and bullet spindrift, but for now, we’ll keep things simple.

There are only two major guiding principles to worry about for most longer-range shooting scenarios: gravity and wind.

Gravity

Like political promises in an election year, you can always count on gravity. Fortunately, when it comes to long-range shooting, gravity is simpler than it may seem at first glance. People get all wrapped around the axle about velocity and bullet shape and how those things “defeat gravity,” but those don’t really have anything to do with defying gravity, at least not directly. You see, gravity only cares about how long an object is exposed to it. If you shoot a bullet exactly parallel to the ground and drop one from your hand at the same time, they’ll both impact the dirt at precisely the same instant, although at very different places. It’s all about the amount of time that the bullet feels the effect of gravity.

When you’re shooting long range, you have to predict the impact of gravity so you can adjust accordingly. Remember, the only thing that determines how fast gravity shoves your bullet towards the ground is time, so everything else just determines how much time the bullet is in the air before it reaches your target. The velocity of your ammo is all about time exposure to gravity. The faster the muzzle velocity, the less time the bullet is in the air for any given distance, so the less time gravity can make it drop. The shape of the bullet is also all about time. A more streamlined bullet doesn’t slow down as quickly, so it spends less time in the air before impacting the target. Again, the result is that it will drop less over any given distance than a non-aerodynamic bullet. Another factor that impacts time in flight is atmospheric conditions, although you can simplify that to air density. The denser the air, the more air molecules that bullets bash into during flight, and the faster they slow down. In “thin” air, bullets fly faster, so they aren’t subject to gravity for as much time.

So, gravity is going to happen. The only variable is how much based on the time that your bullet is in flight.

Now let’s talk about how exactly a rifle and scope “adjust” for gravity. But first, let’s go over an easy-to-understand analogy for a hot second. Since the World Series just happened and the Cubs violated the physical laws of the universe as we know it by winning, let’s use baseball as an example. When Cubs’ right fielder Jason Heyward has to throw a fielded line drive to home plate, he has to adjust for gravity, even though he has an awesomely strong throwing arm. Rather than throwing the ball exactly parallel to the ground like a laser beam, he has to throw it upward. If he didn’t, the ball would hit the field somewhere between his starting point and the infield. Because gravity. By “lobbing” the ball higher, he can compensate for the effects of gravity while the ball is in flight so that when it finally gets to the catcher, it’s still in the air and not dribbling along the grass.

The principle is exactly the same when shooting a rifle long distance. While some people refer to a bullet as “rising” at first, that’s not an accurate description. Let’s use a real-life example with actual math to illustrate the point. If you shoot a standard .223 Remington American Eagle cartridge with a 55-grain bullet exactly parallel to the ground, it will leave the muzzle at 3,240 feet per second give or take. By the time the bullet reaches 100 yards, it will have fallen almost two inches below its original path. By the time it gets to 500 yards, it’s dropped 61.7 inches below its original starting point. By the time it gets 1,000 yards downrange, it’s fallen over 429 inches. Clearly, you’d have to shoot from a pretty high tower, or the bullet would have hit the ground after several hundred yards!

To compensate for the expected drop of a bullet over distance, the scope and rifle barrel are angled in such a way that the rifle barrel initially points a bit high relative to the line of sight of the scope. Stated differently, if the scope is aimed directly at that target downrange, the rifle barrel is aimed above that same target. In effect, the rifle “lobs” the bullet towards the target just like Jason Heyward “lobs” the baseball when throwing from right field all the way to home plate.

This angular relationship is the key to understanding the bullet drop principle of long-range shooting. For any given distance, with any given bullet, fired at any given velocity, and in any given atmospheric conditions, there are formulas developed by very smart folks which can predict the gravity impact on the bullet. Once the gravity effect (known as bullet drop) is calculated, it’s a fairly simple matter to adjust the angle between the reticle in your scope and the rifle barrel to “lob” the bullet the correct amount.

Hold that thought for a minute until after we talk about the wind because the angular relationship applies there too.

Wind

If Jason Heyward throws to home plate in the middle of a hurricane, the wind is going to blow the baseball off target. He’ll have to throw into the wind a bit for the ball to find its way to the catcher’s mitt. The same thing applies with long range shooting, and the real impacts are surprising. Let’s look at an example using the same .223 Remington American Eagle bullet. If there is a 10 mile per hour crosswind at your range, and you aim directly at your target, the wind is going to blow that bullet sideways. For close targets, the effect of wind will be hardly noticeable. At longer ranges, however, you better plan for some sideways drift. Here are some real numbers. At 100 yards, the wind will have blown the bullet just .91 inches to the side of your bullseye. At 500 yards, it’s moved 28.4 inches and at 1,000 yards, it’s blown a whopping 152 inches off target. That’s almost 13 feet! So, just as with gravity, you have to make angular adjustments for the wind when shooting at distant targets.

How much do you have to adjust? That all depends on the bullet shape, the velocity, and of course, the wind conditions. While gravity is a constant thing where the impact is determined by time, bullet shape and weight attributes determine how much impact the wind has. Imagine holding up a sheet of cardboard against a crosswind. The wind will want to blow that all over, right? Now hold up a sewing needle. The same wind won’t have much of an impact because there is much less surface area on the needle. This is why some bullet designs claim to “buck the wind, ” and they aren’t impacted as much.

Fortunately, there are complex mathematical models available to help shooters estimate the impact of the wind based on the specific bullet they’re shooting, the velocity from their rifle, and the current atmospheric conditions.

Calculating wind and bullet drop for Long Range Shooting

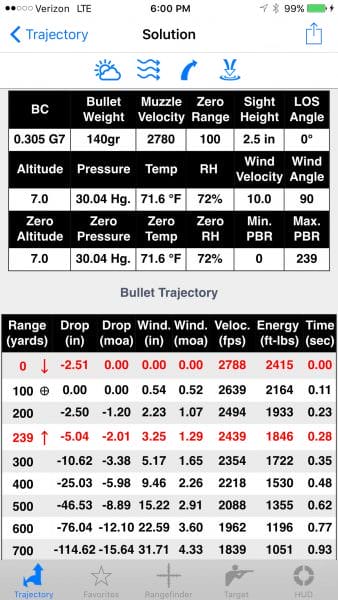

The math behind this stuff is daunting. Fortunately, we live in the age of smartphones and nifty little electronic devices, so all you have to do is plug in numbers. There are plenty of devices, like Kestrel Ballistic weather meters and ballistic computers, smartphone apps, and websites, to help you calculate all this stuff without using a programmable calculator.

These ballistic tools will tell you exactly how many inches to compensate for gravity and the wind at specified distances. That’s helpful information, but it doesn’t help you make adjustments to your scope. Scopes adjust based on angular measurements called minutes of angle and milliradians. That’s a whole new topic, but fortunately, it’s a lot simpler than it sounds. We’ll get into that next time, so stay tuned for part two where we’ll get into milliradians, minutes of angle, and how to adjust scopes using those concepts.

About the Author

Tom McHale is the author of the Insanely Practical Guides book series that guides new and experienced shooters alike in a fun, approachable, and practical way. His books are available in print and eBook format on Amazon. You can also find him on Google+, Facebook, Twitter, and Pinterest.

Lots of variables. Even for mid range shots like 1,000 yds. there are lots of variables. The more variables you can master the better long range shooter you will be. A good 20 m o a ramp mount will help you a lot as distances grow, your scope has a limited amount of adjustment available so consider it before going for distance shots. You must start “in fact”. Bullet velocity, ballistic co efic,, height of c/l scope above c/l of bore and EXACT ZERO @ EXACT DISTANCE. Down to the inch from muzzle to target if you can do it.… Read more »

The best way to (without all the toys and tools for wind, mirage, sun, sun angle, gravity, Coriolis effect, “junk” now available for sniper wannabees) to learn how to get on a target consistently and precisely at those 1,000 yard distances is to shoot on a known distance range (a lot like you see the military doing) with a decent wind flag, study the conditions (especially mirage effects) and note each shot fired and impact compared to what you saw through the sights and or spotting scope when you fired (and when you fire everything must be done right). When… Read more »

Three/seven year old article. Geez Wild Bill, you have been on here for a while!!! Well, lets add something more into it that you should think about before you start talking amount of drop and shift from the wind. The first thing you need to consider is what caliber is it. Do I want to shoot 1,ooo yards or one mile or more. Your friendly 308 AR10 is not going to go a mile. Then while thinking about that, you need to consider not only caliber, but you need to consider barrel length. The longer the barrel the more accurate… Read more »

Tom: I will NEVER, at my current age or probably any other be able to do all the calculations necessary to be a good long distance shooter. However, your articles are well written and even as math challenged as I am I appreciate them. I’ll stick with Kentucky windage but thanks for great articles.

Good Article

Thanks Tom,

This same ‘wind & drop’ is exactly what I kept trying to explain to my Drill Instructor in PI in 1965. If anyone knows Sgt. Maurice Blanchered from Platoon 213, would you kindly forward this article to him….;)

Great article! The simplification takes much of the worry out of long range shooting and provides confidence to the shooter. Thanks!

When you get right down to it, your 200yd zero on your .308/5.56 is going to take care of BLM/Antifa/blue helmets when they come down the street thinking they can burn down your street like they did the blue cities run by Democraps. So far every time they have ventured out of their sanctuary cities, they have looked down the barrels of real America, Joe Biden’ed their pants and run home like the cowards they are. When they poke the bear for the last time, Waste Management is going to have to get a lot more trucks.

I have noticed the effect of crosswind plinking steel targets at 25 yards with a .22.

I have run steel out to 700 yards but a 1000 is a stretch I have not achieved yet and may never . Just being realistic !